Nonprofits & Activism

The real-life superheroes helping Syrian refugees | Feras Fayyad

Visit to watch more groundbreaking talks from the TED Fellows. With his films, he’s on a mission to separate the facts about refugees from fiction, as a form of resistance — for himself, his daughter and the millions of other Syrian refugees across the world. A harrowing account, a quest to end injustice and a…

Nonprofits & Activism

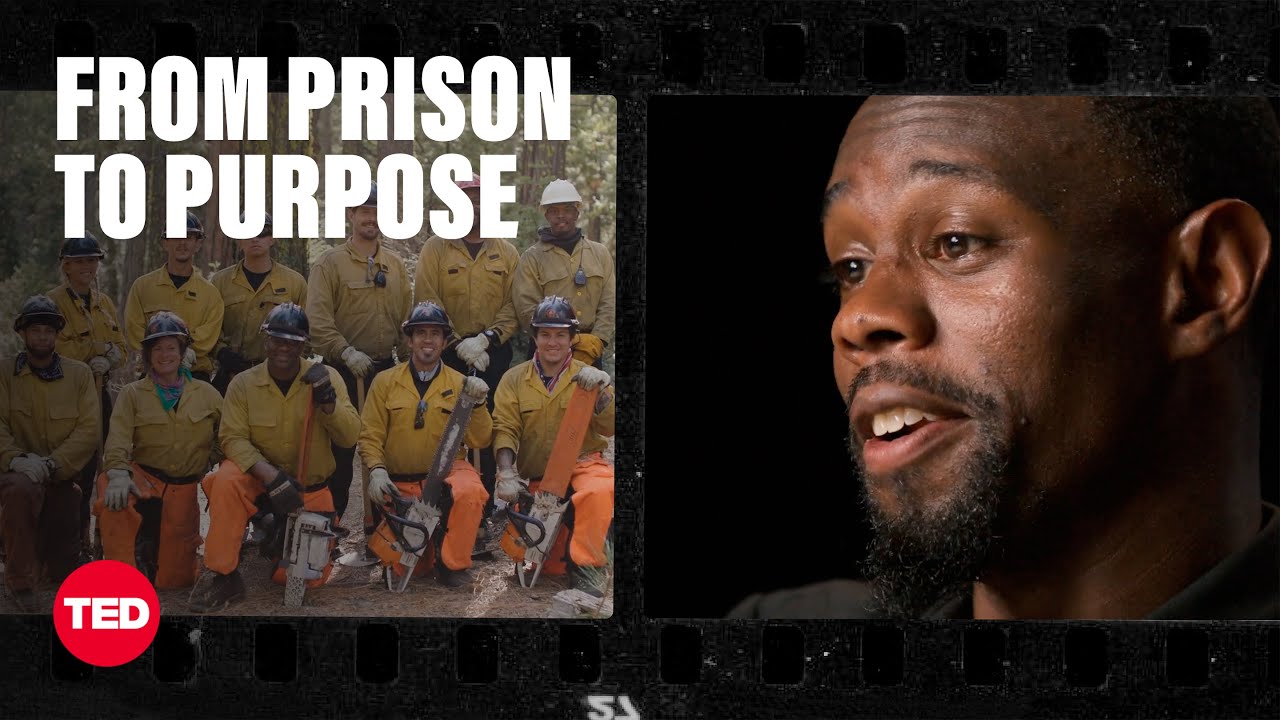

From Prison to Purpose Through Wildland Firefighting | Royal Ramey | TED

When wildfires rage in California, incarcerated people are often on the front lines fighting the flames. TED Fellow Royal Ramey was one of them. He shares the story of how doing public service in prison inspired him to cofound the Forestry and Fire Recruitment Program, a nonprofit helping formerly incarcerated people become wildland firefighters —…

Nonprofits & Activism

The Recipe for a Healthy Climate Starts at the Dinner Table | Anthony Myint | TED

Why aren’t restaurants part of the climate solution? This question inspired chef Anthony Myint to go from opening buzzy pop-ups to pushing for a shift to regenerative farming practices in the food system. He explains how it didn’t go the way he expected at first — and how restaurants are now teaming up with farmers…

Nonprofits & Activism

To End Extreme Poverty, Give Cash — Not Advice | Rory Stewart | TED

Are traditional philanthropy efforts actually taking money from the poor? Former UK Member of Parliament Rory Stewart breaks down why many global development projects waste money on programs that don’t work. He advocates for a radical reversal rooted in evidence: giving unconditional cash transfers directly to those in need, a method that could unlock the…

-

Science & Technology5 years ago

Science & Technology5 years agoNitya Subramanian: Products and Protocol

-

CNET5 years ago

CNET5 years agoWays you can help Black Lives Matter movement (links, orgs, and more) 👈🏽

-

People & Blogs3 years ago

People & Blogs3 years agoSleep Expert Answers Questions From Twitter 💤 | Tech Support | WIRED

-

Wired6 years ago

Wired6 years agoHow This Guy Became a World Champion Boomerang Thrower | WIRED

-

Wired6 years ago

Wired6 years agoNeuroscientist Explains ASMR’s Effects on the Brain & The Body | WIRED

-

Wired6 years ago

Wired6 years agoWhy It’s Almost Impossible to Solve a Rubik’s Cube in Under 3 Seconds | WIRED

-

Wired6 years ago

Wired6 years agoFormer FBI Agent Explains How to Read Body Language | Tradecraft | WIRED

-

CNET5 years ago

CNET5 years agoSurface Pro 7 review: Hello, old friend 🧙